My last article was all about the single biggest problem in bowling green maintenance…thatch, that sometimes thick mat of debris just under the turf. Sometimes hard as a brick and dry as a bone. And at other times as wet and soft as a sponge, making it impossible to prepare the surface of the green to any level of acceptable performance for any reasonable length of time.

Sometimes it seems that thatch is out to get us. No matter what we do, it always seems to come back thicker and wetter and smellier. It causes the green to be slow, bumpy, disease ridden and unpredictable.

But here’s an interesting fact about thatch:

It’s largely man made!

You read that correctly, when left to its own devices, turf grass will produce very little build up of thatch. Sceptical? I can prove it.

As a greenkeeper of some 40 years now, I’ve observed the following phenomenon repeatedly.

On grass areas where there is little or no human interference in the form of excessive fertiliser and pesticides, such as in meadows or parks, the thatch layer will almost always be at the optimum level for a continued healthy turf/soil eco-system. This is due to the soil/plant relationship being in balance; a strong and sufficiently lively soil microbe population releases nutrition from the thatch layer as it decomposes naturally.

As we move to areas that are subjected to progressively higher maintenance, the thatch layer is likely to become thicker and denser and therefore needs more intensive management if the turf/soil relationship is to be kept in balance.

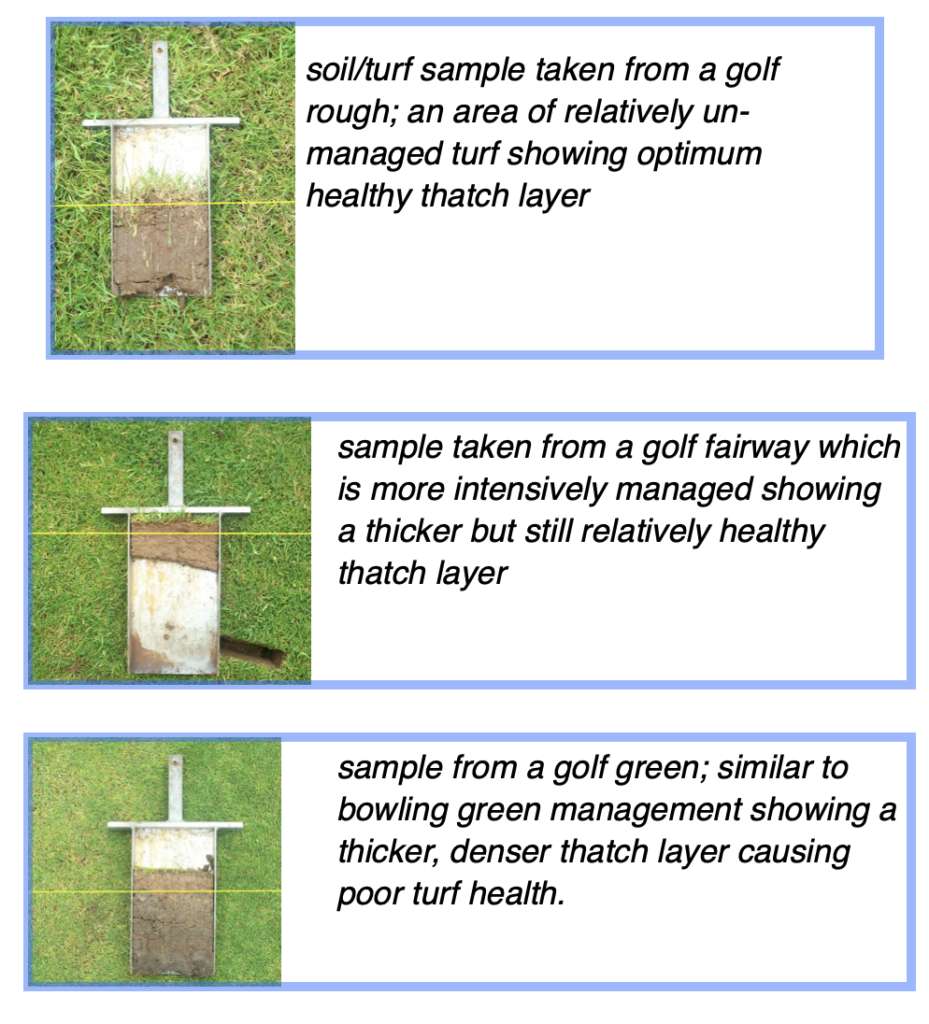

This can be observed by taking samples from a variety of grassed areas and comparing them to your bowling green’s thatch layer; rough meadows and areas such as the roughs on golf courses being the most natural and healthy areas and greens usually being the least healthy and in need of the most remedial work to keep them right.

To illustrate this effect I took some photograph’s on a parkland golf course I was asked to advise on:

The samples in the photos were taken from within a 10 metre radius. I’ve added yellow lines to make identifying the thatch layer easier.

Thatch, which is really only discarded dead parts of the plants, like leaves and roots, is always being produced by our grass plants and is actually an essential part of the ecology of grasslands. This dead plant material is recycled into essential nutrients required by the living plants to grow new green tissue. The recycling is done by a host of soil organisms like worms and micro organisms (microbes), such as fungi, bacteria and nematodes. In healthy, living soil there can be up to 1 billion of these microbes in every teaspoonful of soil!

The build up of excessive thatch layers is largely due to the accepted greenkeeping traditions and myths that have been promoted for at least the last few decades. We’ve been led to believe that we are in control of nature, and that we can deal with any problems that it throws at us through the application of products and chemicals. Fertilisers for more growth and pesticides for any diseases or pests that spring up from time to time.

Most of these fertilisers are inorganic and have an acidifying effect on the soil. Combined with compaction this can lead to anaerobic conditions and the beneficial soil microbe population plummets. Suddenly thatch isn’t being degraded quickly enough and it starts to build up rapidly.

Furthermore, the continual addition of sand to bowling greens that are already very sandy after decades of top-dressing, leaves the soil inert and lifeless.

An artificial surface?

In order to produce a tight, dense sward of one or two species of grass suitable for bowling we are essentially trying to produce what is a largely artificial surface…or are we?

The original locations deemed most appropriate for golf, due to the fine, dense and firm turf made up of just one or two species of fine grass were the links lands near the coast. Continually close mown by sheep and rabbits and fertilised by only the grazers’ droppings, this type of turf largely looks after itself. That’s because it is a fully self sufficient eco-system.

These very same, links land type soils are the ideal growing medium for bowling greens too. However, repeatedly adding sand to your soil doesn’t make it a links soil.

Ecology mindset

Bowls clubs who start on a greenkeeping program that recognises that the green is a living eco-system and not merely a series of problems and symptoms to be killed or manipulated, can produce very fine greens with very low costs.

With this type of objective and evidence based greenkeeping, greens can quite quickly be turned around to provide consistently high performance surfaces that are firm, smooth and true. The bonus is that the major expense of top-dressing can be dispensed with as the greens are in most cases so full of sand that no further application is required and a long period of restoration of humus, through the natural decomposition of thatch can begin.

Incidentally, excessive thatch is the single biggest cause of poor green levels.

The best time to start this process is now. Yes, even in the dead of winter, the good work to improve our greens can commence at pace.

Aeration

In the absence of soil oxygen, thatch will remain thick, dense and smelly. It will encourage disease outbreaks in winter and keep the surface wet, and spongy.

By getting air into the soil now, we can improve oxygenation, release toxic gas build up and start to boost the soil microbe population.

Mini tining and solid tining are very effective methods for this, but by far the best method in winter is regular deep slit tining, which has the added effect of relieving compaction deeper in the soil.

Provide for your microbes

The addition of carbohydrates to the soil will help your microbes to multiply, by offering them a readily available food source.

This can be achieved through the application of bio stimulants based on seaweed or molasses.

Don’t shoot the messenger

As greenkeepers we are constantly bombarded with new products to deal with this problem or that.

Fungicides are a great example of this.

We’ve been taught that fungus is bad and that fungal diseases such as fusarium, somehow make their way to our green to spoil all of our good work.

The fact is that there are many different fungi in our soils and all of them have a role to play in the ecology of the bowling green. Many of them are directly beneficial to the health of our turf.

We get fungal disease outbreaks when we tip the balance of the green eco-system in favour of one or other of the pathogenic fungi such as fusarium.

The usual reaction to such an outbreak is to blanket spray a fungicide, which by its very nature kills all of the fungi it comes into contact with, regardless of whether they are beneficial or pathogenic.

In the early stages of my performance bowling greens program I encourage greenkeepers to apply only spot treatments of fungicide for any disease outbreaks they are concerned about. This at least gives the other fungi a fighting chance to multiply.

Free ebook

You can pick up a free ebook at bowls-central.co.uk to help you gain a better understanding of bowling green ecology.