Localised Dry Patch is a common problem on greens in summer and it can take a while to conquer it. Could some of our traditional management practices be making it worse?

Top dressing is a very common practice on UK bowling greens in autumn. It has become a bit of a tradition for clubs to make the sizeable investment in at least 3, but in a lot of cases up to 10 tonnes of the sandy topsoil medium in order to spread it on the surface of the green in the hope that it will improve the green. And after a long bowling season when the green is looking worn and tired, clubs need no excuse to see and be seen undertaking such a drastic and obvious maintenance operation. Surely such a heroic undertaking will make the green better?

Well, for how many years have clubs been saying that same thing? Around the country the results speak for themselves; greens are generally not getting better, especially in terms of predictable high performance. Sure there are lots of anecdotes about how the green played better on opening day than it ever had before, but real evidence of long term improvement just isn’t available and that is because there hasn’t been any.

Greens are harder to maintain now, less predictable and more complex and baffling than ever. Just when you think you’ve nailed it and the green is in perfect shape for the championship, the very next week it looks and plays like it came from a different planet.

One of the biggest culprits for this maddening lack of consistency is sand top-dressing. In a previous post I did some rudimentary maths on the sheer volume of sand that our greens now contain and a conservative estimate is that in a lot of cases the top 100mm is made up of 90% or more of sand.

Now that is a big problem that will only go away if we make brave choices and go against tradition in our green maintenance decision making. The problems caused by this deluge of sand are many many fold and include inert, unmanageable soil, excessive thatch build up, poor green speed and smoothness, lack of plant nutrition, very low soil microbe populations, increased fungal disease out breaks, bumpy and uneven surfaces, layering and rootbreak…I could go on. You will find a full list here.

By far the most grotesque of these problems and the one that has resulted in more greenkeeper sackings, committee changes and sleepless nights is Localised Dry Patch.

Localised Dry Patch (LDP) is one of those problems that seems to just appear overnight on your green and it can devastate a club’s entire bowling season. The really maddening part for most clubs is that this will be the first time that they’ve encountered a big issue that can’t be made to look better through the purchase of a miracle product. LDP is also the issue that finally helps clubs to start understanding that a lot of the greenkeeping they’ve been doing is wrong. LDP doesn’t go away easily and it doesn’t even go away when it appears to have gone away. The effects of it are masked somewhat by the prolonged wetting of winter, only for it to reappear in June seemingly without warning.

What does LDP do?

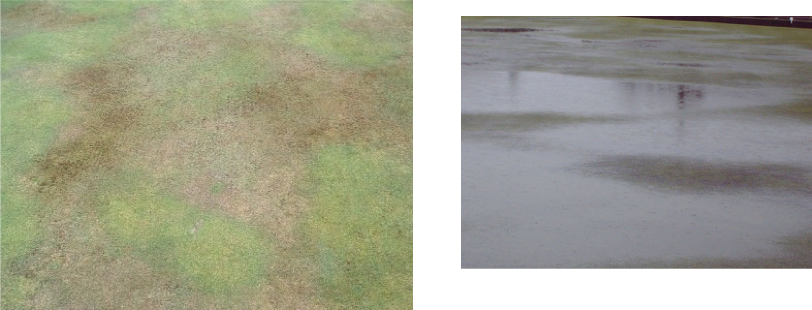

LDP causes large areas and even whole greens to resist moisture. The soil has become Hydrophobic. Water will lie on the green surface for a long time and the soil underneath will remain powder dry and unable to support plant life. The result is large brown patches on the surface where the thatch eventually dries out so much that it becomes hard and brittle. At this point it will shrink to below surface level, causing large pans of low lying turf which of course affect the performance of the green to a level that is unacceptable. Temporary measures such as sarrel rolling and wetting agent application can help to get water into the green, but the water still wont adhere to the soil particles below making sure that most of the irrigation water runs straight through to the drains.

What’s going on ?

If you’ve ever seen a bug on a pond, you will notice that it seems to be walking on water and that somehow it hasn’t actually penetrated the surface. This is because water has a surface tension and this plays a big part in hydrophobic soil. In fact many of the products that are sold to help with LDP called wetting agents, act on the water to reduce its surface tension, making it easier for it to be absorbed by hydrophobic soil.

However, LDP is more complex than just soil that has dried out too much. The mineral component of our soil is made up of sand, silt and clay and in many cases on bowling greens the individual sand particles can become coated with an organic, waxy substance.

Adhesion and Cohesion

Water has 2 key properties. The first is adhesion which describes the ability of water molecules to stick to a solid surface like a sand particle. The other is Cohesion which describes the attraction of water molecules to other water molecules. It is cohesion that allows water droplets to form.

So, on a surface that resists the adhesion of the water molecules like for example a freshly waxed car, the water will remain in tightly bound, round droplets and wont wet the car. Instead the droplets will just roll off the car. The same thing is happening on the soil particles of soil affected by LDP which is caused by the the fact that there is just too much sand in the green.

When Adhesion is greater than Cohesion, then gravity will pull the water molecules apart, making the water droplet spread out and wet the surface. However, when Cohesion is greater than Adhesion then the opposite will happen, The water molecules will remain strongly bound to each other and no wetting will occur.

This is illustrated by the coloured water drop experiment on this hollow core taken from an LDP affected green. This experiment measures the time it takes the soil to absorb the water. LDP affected soils can take a very long time to do this, making it likely that the water will have evaporated or run off to the drains before it can be absorbed. Look at how well rounded these water droplets are. This shows that the force of Cohesion is greater than that of Adhesion:

The microscopy image below shows a clean sand grain that hasn’t been coated with the waxy organic substance:

Now we have a microscopy image of a sand particle with the troublesome coating. In a test on the hollow core this grain came from, the water drop penetration test result was greater than 2500 seconds:

Conclusion

A waxy organic coating excreted during the natural breakdown of organic matter creates a hydrophobic layer which prevents water from rain or irrigation being absorbed by the soil.

Sand dominated soils are more likely to be affected and severe cases of hydrophobia in soils can be seen on many bowling and golf greens where sand has been routinely used as a topdressing or incorporated as the major component by volume of top-dressing composts.

Bad outbreaks of LDP can occur where as little as 3% of the sand fraction is affected.

Cutting out the annual top-dressing for most greens will result in improved green health cumulatively over the years that follow the cessation. Green performance will become more predictable and manageable. This is the foundation of the program I detail in Performance Bowling Greens.

Materials to help with Dry Patch