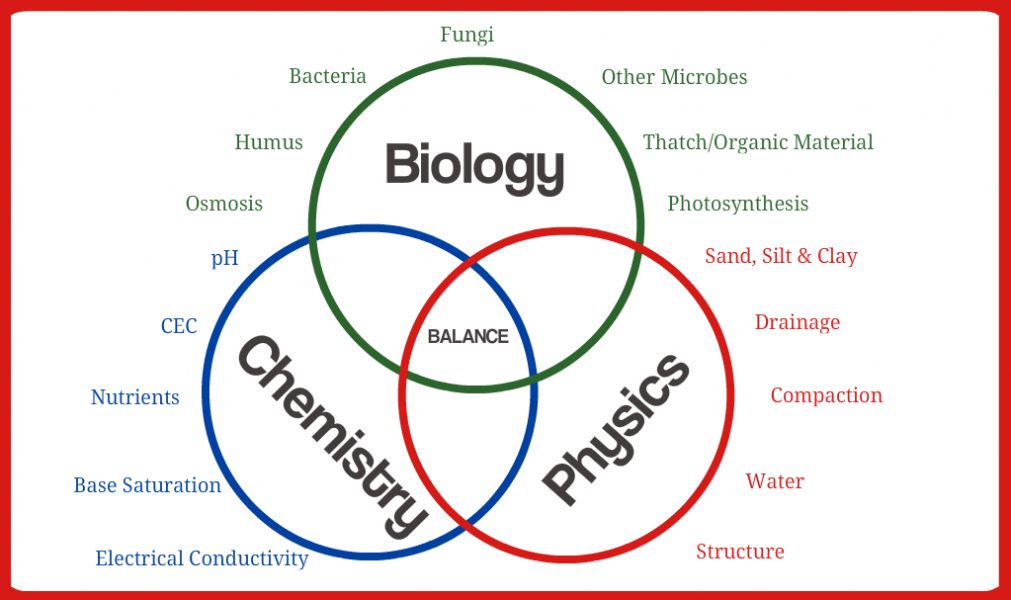

Bowls Central Academy Membership offers a series of new benefits to members, most importantly a growing range of online educational courses in Greenkeeping and related subjects.

Current Courses Include:

Academy Membership Benefits

Of course I’ve given a great deal of the focus of Academy Membership over to education and the online study courses, but there is a list of other benefits for members.

The available courses, levels of study and other member benefits will be added to on a regular basis.

- Online educational courses in Greenkeeping and related subjects

- Free Soil Analysis for your green including a full report and recommended greenkeeping programme specifically tailored to your green

- Free Delivery on Website Orders

- All Bowls Central eBooks free to members

- Permanent Greenkeeping Materials Discounts on all greenkeeping materials. Currently 5% off Equipment, tools and rootzone improvement materials and a huge 10% off everything else in the Bowls Central Shop

- Full access to a growing library of over 300 greenkeeping articles

- Further benefits and member only offers will be added on a regular basis