Last time, I introduced the subject of Disturbance in bowling green ecology and maintenance. I finished by posing the question; How can we use disturbance theory to our advantage in our quest to create a Performance Bowling Green?

To answer that, let’s look at what might constitute Disturbance in the average bowling green. As greenkeepers we actually have an impressive amount of potential influence we can bring to bear on the turf environment; some good and some bad. We can think of these influences as pressures and by applying them with the right force we can manipulate the bowling green eco system (to some degree) to our advantage.

Last time we also discussed Stress factors, which when compared with physical disturbance from our machinery and bowling, can seem innocuous, but the overall affect of say LDP can easily be more damaging to our turf in the long term than an obvious physical disturbance like hollow tining.

Every day Greenkeeping and bowling can have a high disturbance value and put the very grass we are tending under a lot of stress. Mowing, verti-cutting, wear from bowling, pests, diseases, disorders, aeration, top dressing, water and nutrient availability and soil pH can all cause stress to a greater or lesser degree and this will change depending on grass species, general green condition, weather and soil type/condition.

Well the answer is clear then isn’t it? Maybe if we just do nothing (which is the right thing sometimes) the green will improve on its own. If we had unlimited time and didn’t need the green to be prepared for bowling, then I would say absolutely yes, leave it alone, bar maybe a sheep or two and it would sort itself out easily. There would be no thatch, compaction or LDP either. But we don’t have that luxury so we need to intervene to get our green in the shape we want, especially if our green has been subjected to what has become conventional or traditional greenkeeping.

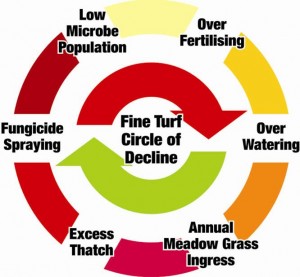

The transition from a failing green that is deep in the grip of the Circle of Decline to the Nirvana that is a Performance Bowling Green is something that needs a fair deal of skill and a great deal of patience and consistency of approach. Once we are in utopia with a Performance Bowling Green we can start to think of backing off on the heavy, physical maintenance and begin to implement a low disturbance diet.

Once we have reversed the process of decline the bowling green can and will improve quickly, but it’s at this time that we need to exercise caution and stick with the program, avoiding slipping back into the old patterns of maintenance at all costs.

Using Stress to Our Advantage

At that stage we can start to use the stresses of disturbance to our advantage. The plan is to create a healthy, settled green first and then put the thumb screws on the undesirables like annual meadow grass slowly but surely, all the time making sure that the techniques and intensity of maintenance we use don”t put the bent and fescue component of the sward under undue stress.

Disturbance can be used to get the ball rolling on green transition from 100% annual meadow-grass turf with squidgy, thick thatch at the turf base over a claggy clay soil. The first steps would include making sure there is physical drainage to take away excess water.

The program would then move on to the renovation phase which would start with aggressive compaction relief. Then a series of operations to physically remove thatch would follow and this could include, intensive core aeration, deep slotting/scarification and maybe even top dressing with sand (yes you read that correctly) if the conditions demanded it.

When in the grip of the Circle of Decline, greens in this condition usually need a high Nitrogen input just to tease a result out of them for play, so the fertiliser program will definitely need a revisit to reduce this. Watering will usually be too high also so we have to tweak and jiggle the program a little at a time in order to maintain grass cover during this major transition.

Finer surface aeration like verti-cutting will be intensified as will sarrell rollling and it will become increasingly important to keep the mower razor sharp with zero contact blade settings to maintain the health of the turf plants.

The Phases of Recovery

In Performance Bowling Greens I split the recovery and on going delivery of performance into 3 distinct programs of work that may or may not be used in parallel depending on the overall condition of the green in question. These are Baseline Maintenance, Renovation Maintenance and Performance Maintenance, leading to phase known as Continuous Improvement

The process of transition from a predominantly annual meadow grass, thatchy, compact and anaerobic, sickly green to a Performance Bowling Green is detailed in my eBook Performance Bowling Greens below