My post yesterday looked at the huge extent to which the top 100mm (4inches) of our greens have been subjected to sand over the previous 3 or 4 decades.

Today I’d like to elaborate a little on my thinking about taking a green from that state to one of High Performance.

The recovery process is based on encouraging that same top 100mm to return to a state that is akin to a natural, healthy living soil. This of course takes time as we are actually waiting for nature to produce more organic matter to ameliorate the sand to bring the soil back to a state where it can support a large, thriving population of soil microbes.

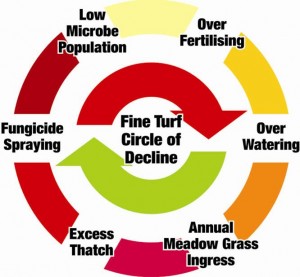

If you imagine my sketch of the “Circle of Decline” as a water wheel spinning fiercely in a clockwise direction; in other words out of control due to inappropriate maintenance. Each application of sand, pesticide, excessive N fertiliser, etc only serves to set the wheel spinning ever faster in the wrong direction.

The performance greens program is aiming to make the wheel turn in the opposite direction so a lot of the effort at the beginning is simply to slow the wheel down gradually until it is eventually stopped. The program then needs to get the wheel to start turning in the other direction.

Once it starts to turn in the right direction every bit of the correct maintenance program just makes it go faster and faster, so although the recovery process is slow at first, it builds very quickly once things are turned around.

We then start to see the action of what I am going to call the Circle of Improvement due to lack of imagination!

Every ounce of new Read more